As the COVID-19 vaccine rollout continues in Australia, the topic of vaccine confidence (or vaccine hesitancy) has emerged in conversations all over the country, from boardrooms to barbecues.

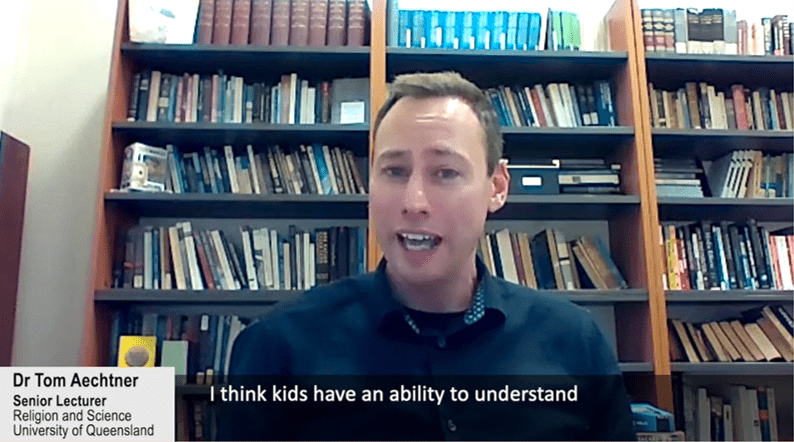

Dr Tom Aechtner is a Senior Lecturer in Religion and Science, at the University of Queensland (UQ), and has conducted research on vaccine hesitancy in Australia and overseas. Dr Aechtner has led the development of an online open access course at UQ, AVAXX101.

In March as the pandemic was just beginning in Australia, Dr Aechtner was working on a pro-vaccination website (unrelated to COVID-19):

“I was working with copywriters and with Internet designers and they’re all saying ‘well this will kind of kill the need for pro vaccine websites because everyone’s going to want a vaccine.’ In response I said, actually it’s probably going to augment the same sort of vaccine conspiracy theories that we saw before the pandemic. We’re going to see fears actually be accentuated rather than being alleviated, and I feel like that’s what’s happened.”

It could be argued that there has never been greater need for confidence in vaccines, so now when we need vaccination to protect our community and economy, why are we seeing uncertainty, mistrust or simply apathy?

Vaccine hesitancy is not new

Since the first vaccine was developed and came into use there has been opposition to vaccination. The UK’s Vaccination Act of 1853 which made smallpox vaccination mandatory for young children ignited criticism and protests. In 1867 the Anti-Vaccination League was founded based on concerns over infringement of civil liberties.

In Australia, the Government has said that they will not make COVID-19 immunisation mandatory, but there has been talk of ‘immunity passports’ and with the background of the ‘No Jab, No Pay’ policy, the question of whether vaccination could be required in certain circumstances has not been entirely put to bed.

A victim of their own success

Alongside civil liberties arguments, attitudes to vaccines are complex and are not only based on conspiracy theories and misinformation. Dr Aechtner points out that giving people the facts alone is not enough to convince them of the safety and efficacy of a vaccine. And the speed of vaccine development may be a victim of its own success.

“We’ve never had a situation in which people have had such expectations for a quick roll out of vaccines and development of vaccines. The rapidity of the vaccine development during the COVID-19 pandemic has been incredible, it’s been phenomenal to see, and that’s also led to some people’s anxieties because they see this relatively quick development of new vaccines. We’ve never had this kind of scrutiny of vaccine development and rollout in social media and in news cycles.”

As border controls and lockdowns in Australia have been largely effective at keeping infections and the death toll low overall, the effects of the disease itself are far less immediate and obvious. For other vaccine preventable illnesses this is also true, Dr Aechtner explains;

“We don’t see what vaccines do after they do their work, so vaccines are a victim of their own success. When we have societal wide vaccination, even if we have people that are opposed to vaccines, when you get enough people vaccinated, we don’t see those vaccine preventable diseases anymore. So then people think ‘Oh, maybe the risk of getting vaccinated is worse than the vaccine preventable diseases’, because they haven’t witnessed the vaccine preventable diseases for themselves.

I didn’t see polio in Canada growing up, I never saw the effects of polio, I only saw polio when I travelled overseas as a university student and I went to West Africa, and people in West Africa were just desperately wanting the polio vaccine.”

Changing minds

Understanding the concerns people have and addressing them is important, but how we communicate those messages is also key. Dr Aechtner’s top tips for communicating about vaccination include:

Dr Aechtner notes that the demand for vaccines can also easily change as events unfold, even in Australia:

“Perhaps the demand for a vaccine isn’t quite there yet across the population, because Australia has had one of the most successful responses towards the pandemic in which we’ve really lived quite normally in most parts of Australia, since the middle of last year.

The interesting thing is there’s been some local research I’ve been part of here, where we had a snap lockdown in Queensland and people had to wear masks, and people’s interest in getting vaccinated rose just because they didn’t like wearing masks.”

Dr Aechtner’s vaccine hesitancy course AVAXX101 was initially developed for healthcare workers as those most called upon to discuss vaccination with their patients. Through his research, he discovered that no other course existed that was widely available addressing this issue. During the development process Dr Aechtner recognised that the demand extended beyond those in healthcare and the course is therefore available to anyone. There are currently participants from over 70 countries.

If you want to learn more about vaccine hesitancy sign up for AVAXX101