Last week the Australian Medical Association (AMA) released a timely statement calling on the Federal Government to launch an online advertising campaign to combat health misinformation on the internet. With the battle against COVID-19 at a critical stage, the speed at which the world gets on top of the virus depends as much on winning the argument as it does the science, and effective messengers will be key to success.

“…the internet has the potential to significantly magnify health misinformation campaigns, as people can easily absorb misinformation delivered directly to them through advertising, celebrity influencers, and people in positions of power,” AMA President Dr Omar Khorshid said.

“We have seen this with the anti-vaccination movement, and the countless conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 pandemic that circulate constantly on the internet.”

We’re in an “infodemic”

Indeed, so prevalent has health misinformation been during the pandemic with the anti-vaxxer movement, conspiracy theories and promotion of unproven treatments, that the Director General of the World Health Organisation (WHO) Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus declared: “We’re not just in a pandemic; we’re in an infodemic.”

A once in a century pandemic falling during what feels like the peak of the post-truth era was always going to present communication challenges for health authorities. People in positions of influence routinely peddle health misinformation to large platforms, from former US President Donald Trump to Liberal Party MPs Craig Kelly and George Christensen.

What’s proved particularly challenging for health experts is communicating to the public with imperfect evidence; research is still playing catch up with an evasive virus one year on.

This has led to mistakes and U-turns, the WHO’s U-turn on masks is perhaps the best example of this. Such incidents embolden online communities to question experts and legitimise their conspiracy theories.

We’ve also seen health experts openly disagreeing with each other. Last week, health groups including the Australian and New Zealand Immunology Society urged the government to pause the role out of the AstraZenca vaccine due to concerns over its ability to achieve herd immunity.

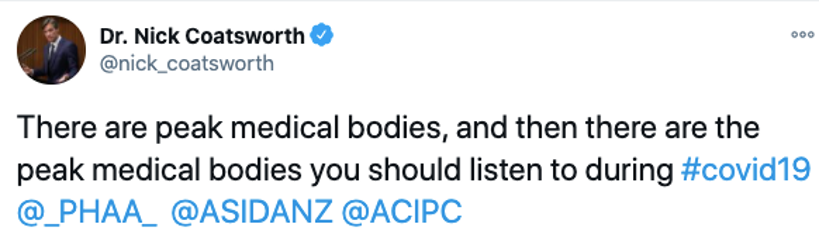

This prompted Chief Medical Officer Paul Kelly to issue a stern rebuttal in a press conference. The tone of the response captured succinctly in a Tweet by one of his deputies, Dr. Nick Coatsworth:

‘Don’t just listen to experts, listen to the right experts’, more simply put.

What Dr. Coatsworth is trying to convey here is an important lesson in communications; selecting the right messenger is critical, especially in a hierarchical profession like healthcare.

This will be especially important to the success of the vaccination program and should be a feature of all healthcare communications campaigns.

Establishing trust is key, here are some of our trusted messenger essentials:

Authority

The media craves comment from experts, which means sometimes trading off between the messenger you want versus the messenger the media and public wants to hear from.

Questions you should be asking:

Will this messenger be viewed as a genuine expert?

Do they have an impressive title? – e.g. Dr. or CEO

What are their achievements?

What is their life story?

This is what behavioural scientists call “hard messenger traits” (authority, status-driven). An often-used demonstration of this is the film The Big Short. Have you ever wondered why Michael Burry (played by Christian Bale) fails to convince investors of his prediction of an imminent subprime mortgage crisis?

The answer, according to behavioural scientists, is because the socially awkward Burry lacked hard messenger traits to be sufficiently convincing, even though his message was backed by compelling research.

Messenger authority was present from the start of the pandemic. Medical and health officers were put forward to answer health questions in almost all federal and state government COVID press conferences. That so many of us can name them in 2021 is quite astonishing.

Diversity

Australia is multi-cultural nation. According to the 2016 census there are around 200 languages spoken here.

For the vaccination roll out, it would be advisable for those in charge to consider who is delivering the message to certain communities.

How much more likely is it that a community will listen to a community leader, who shares the same cultural identity and speaks the same languages, than they will listen to say their local MP?

This is particularly important in advocacy campaigns. For example, if you’re campaigning for the health of indigenous groups, indigenous voices must be leading from the front.

Again, there is plenty of behavioural scientific evidence to suggest human beings are more likely to trust someone of a similar cultural background as their own. Hardly surprising when you think about, but it is surprising how often those in positions of power get the diversity balance wrong when they communicate.

Influencers

Influencers can also be powerful carriers of your message. It’s why after so many years, brands continue to pay celebrities gross sums of money to endorse their products.

For the vaccine roll out it will be interesting to see if the government looks to a diverse range of influencers. This could be particularly important for those “in the middle” people that will need convincing. If a young nervy-vaxxer sees someone they admire endorsing a vaccine, it might be enough encouragement for them to follow.

This was precisely the approach adopted by the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK ahead of its mass vaccine roll out late last year.

The concept of influencer communication should be applied to all healthcare campaigns, where the involvement of health consumer organisations, key opinion leaders and influential patients can make all the difference in achieving the desired outcomes. It removes the “you’re just saying that to make money” preclusion and forces those you’re trying to persuade to consider the argument for your medical device or product.

That is to say: don’t let your message be dismissed before it’s even been heard.

*Behavioural science references drawn from a variety of sources, most of which can be found in the book: ‘Messengers: Who We Listen To, Who We Don’t and Why’ by Joseph Marks and Stephen Martin.

If you would like to find out how to build effective messengers in your company or organisation, schedule a 20-minute discovery call with one of our team members.

Image credit: ABC