Australia is a land known globally for many things. Our magnificent nature, our unique wildlife and our sporting prowess to name but a few. However, one item which flies under the radar is our contribution to the STEM fields, in particular when it comes to medical technologies. As part of National Science Week 2023, London Agency takes a brief look at some of the medical breakthroughs that Australia and Australians have played a key role in bringing to the world.

The medical application of penicillin

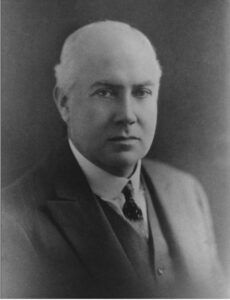

Born in Adelaide on September 24, 1898, Sir Howard Walter Florey helped to change the course of medical history through his work on medical applications for the use of penicillin.

Whilst Penicillin had been discovered by Alexander Fleming in 1928, the active substance was not isolated at the time. Florey’s partnership with Ernst Boris Chain bore fruit when in 1939, they headed a small research team that completed the successful small-scale manufacture of the drug from the liquid broth in which it grows.

In 1940 a report was issued describing how penicillin had been found to be a chemotherapeutic agent capable of killing sensitive germs in the living body. Thereafter great efforts were made, with government assistance, to enable sufficient quantities of the drug to be made for use in World War II to treat war wounds.

This medical breakthrough revolutionised the way infectious diseases are treated today, with some estimates saying it has saved over 82 million lives.

For his achievement, Florey was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1945, alongside Fleming and Chain.

Cochlear Implants

Inspired by his deaf father, Graeme Clark of country New South Wales told his primary school teacher he wanted to ‘fix ears’ when he grew up. Seeing the isolation and frustration his father experienced from living in a world of silence, he pursued this goal with great vigour.

To this end, Clark hypothesized that hearing, particularly for speech, might be reproduced in people with deafness if the damaged or underdeveloped ear were bypassed, and the auditory nerve electrically stimulated to reproduce the coding of sound.

Cochlear Implants, otherwise known as the bionic ear, was first used by Clark for his patient Rob Saunders, reconnecting him to hearing and bringing music into his life.

Today, the Cochlear brand is the global leader in implantable hearing solutions, connecting hundreds of thousands of people all over the world to a full life of hearing.

Gardasil and Cervarix cancer vaccines

Every year, close to 530,000 women worldwide receive the news that they have cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer is the second most common form of cancer in women and one of the deadliest, with most deaths occurring in developing countries.

In the 1990’s University of Queensland researcher Professor Ian Frazer first started developing a vaccine for HPV, along with his colleague, Dr Jian Zhou.

When Zhou unexpectedly passed away in 1999 at the age of 42, Mr Frazer continued their work, going on to bring their vaccine to market in 2006.

In 2006, the TGA approved Gardasil, and only a year later, Australia became the first country that rolled out a national HPV vaccination program.

To put the impact of the vaccine into context, in the first four to five years after the program started, the Cancer Council observed a 77 per cent decrease in the number of 18-24-year-old women with HPV (for the HPV types covered by the vaccine).

Precancerous abnormalities were also observed to have decreased – by 34 per cent in 20–24 year-olds, which means they will be at a much lower lifetime risk of ever developing cervical cancer.

Portable blood glucose monitor

Stanley Clark, an Australian electronics and mechanical engineer saw his daughter Lisa diagnosed with type-1 diabetes in the 1970s.

At the time, children with this type of diabetes could typically only have their blood glucose levels measured in a hospital.

Unsatisfied with this and seeing the emotional toll this was taking on his daughter, Mr Clark set out to create the world’s first portable battery-operated blood glucose monitor.

Mr Clark’s completed device allowed people with diabetes to monitor their own sugar levels by pricking a finger and dropping some blood onto the machine’s testing strip, which would return results within minutes, replacing the need for multiple hospital visits.

Now, portable glucose monitoring devices are commonplace in diabetes management, including CGM devices such as Freestyle Libre.

The Artificial pacemaker

As far back as the 1890’s, it was hypothesised that the human heart could be contracted by applying an electrical impulse to it.

In 1926, Dr Mark C Lidwill, an anaesthesiologist at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, partnered with physicist Edgar Booth from Sydney University, to design and construct a rudimentary pacemaker device that was both portable and could be plugged directly into a lighting point.

The device was capable of making the heart beat between 80 to 120 times a minute with voltages between 1.5 and 120 volts. A medical breakthrough.

One of the most famous early adaptations of the technology was in 1928, when the apparatus was used to revive a stillborn infant at Crown Street Women’s Hospital in Sydney, whose heart continued “to beat on its own accord”, “at the end of 10 minutes” of stimulation.

From this humble beginning, the pacemaker is now a key component of cardiovascular intervention.